Before 1960 the Republic of Korea (ROK) was a war-torn nation with a GDP per capita of $70 – equivalent to that of Ghana.1 The government was weak, and did not have the financial capabilities to invest in large-scale rural development projects.2 With this in mind, South Korean President Park Chung-Hee implemented the Saemaul Undong (SMU) program, or “New Village” Movement in the 1970s.3 The government realized that by providing some support, the people could improve their own living conditions by cooperating with each other.4 With the help of United States foreign aid, this initiative was completely centered around community-led development.5

Between the years of 1970 and 1971, the government of ROK provided 33,267 villages with 335 bags of cement. Based on the SMU process, villagers collaborated to determine what aspects of the community should be addressed with the resource provided. In this first step of SMU the community was mobilized through general meetings, government-led training exercises, and exposure visits. This nation-wide training was required for politicians, government officials, village leaders and farmers in order to appropriately build up capacity and enthusiasm for the SMU spirit.6 Village leaders played a large role, mobilizing their communities to facilitate a change in mindset.

By 1972, 16,600 villages (approximately half of those provided with the cement) were deemed successful by the South Korean government. These villages were sent another 500 bags of cement and one ton of steel rods. Again, the community was responsible for determining how these resources should be allocated. This was important, because the South Koreans are self-proclaimed as extremely competitive. The government’s policy incentivized other villages to compete well, and to even mobilize their own resources in order to improve the status of their community. As a result, the Korean government received a sevenfold return by instilling a self-help mentality.7

Within four years, rural income surpassed urban income for the first time.8 Within nine years, rural income sextupled from 225,800 won to 1,531,800 won.9 Rural poverty decreased from 27.9 percent in 1970 to 10.8 percent in 1978, and women were given a significant role to play.10 Thanks to a major land redistribution movement between 1948 and 1951, communal land formerly belonging to Japanese landlords during colonization was allocated in an egalitarian manner, so that there were many small-farm owners and few landless homes.11 Across the country, thatched huts transformed into sturdy tiled houses.12

By 1974, foreign aid and grants had dropped from 60% to 20% of all investments in ROK. Eventually, the United States phased out their aid program in ROK altogether.13 The SMU Movement adopted the slogan diligence, self-help and cooperation, as active participation and successes grew.14 From this first project, communities were pulled together to be decision-makers of their own community-led development. This process gradually rebuilt both ROK’s infrastructure and national identity.15

The New Village Movement grew into a success based on six separate phases, which the country collectively passed through chronologically.

- Foundation and groundwork (1970-1973)

- Living environments were gradually improved as roads and villages were expanded. Laundry facilities, roofs, kitchens and fences were improved. Income increased as roads provided more agricultural opportunities, and seeds and the division of labor were improved. Attitudes within the community shifted towards a mindset of diligence, frugality, and cooperation.

- During this phase the campaign was introduced and implemented. The government initiated activities, with a top priority in improving living conditions.

- GDP per capita (in USD) increased from 257 in 1970 to 375 1973.

- Proliferation (1974-1976)

- Income increased further, with the proliferation of rice field ridges, creeks, and a mentality encouraging combined farming and common workplaces. Non-agricultural income sources were explored more than ever before. Attitudes shifted further with the help of the Saemaul education programs and due to public relations activities. Living conditions continued to improve, with an improvement in housing and water systems. Village centres spread.

- The program’s scope and functionality grew, increasing incomes and further changing the attitudes within the communities. This kindled an atmosphere of understanding and consensus.

- GDP per capita grew from 402 in 1974 to 765 in 1976.

- Energetic Implementation (1977-1979)

- Rural areas saw the construction of modern houses, which encouraged growth, especially of industrial facilities, agriculture and manufacturing. In urban areas, alleys were paved and order was improved and reinforced.

- This progression allowed for linkages between villages, economies of scale, and an emergence of district unit characteristics

- GDP per capita (in USD) increased from 966 in 1977 to 1,394 in 1979.

- Overhaul (1980-1989)

- Throughout the country the social atmosphere improved – kindness, order, selfishness and cooperation were reinforced. Economic development soared, especially with farming. Resources were better allocated, and credit unions proliferated. The environment was taken into consideration, with parks and roads improved and established.

- The private-sector was revitalized, and there was a more enhanced designation between the government and the private sector. This assisted with inactivity and overlap.

- GDP per capita improved from 1,507 in 1980 to 4,934 in 1989.

- Autonomous Growth (1990-1998)

- With the establishment of a sound atmosphere, ROK improved traditional culture with an emphasis on hard work and stable lifestyles. The people experienced economic recovery then economic stability, particularly with the help of urban-rural direct trade. Autonomous lifestyles became more popular and possible.

- Self-reliance was established, allowing the growth of liberalization and localization. The economic crisis became seen as surmountable, and GDP per capita increased significantly.

- GDP per capita increased from 5,503 in 1990 to 10,548 in 1996.16

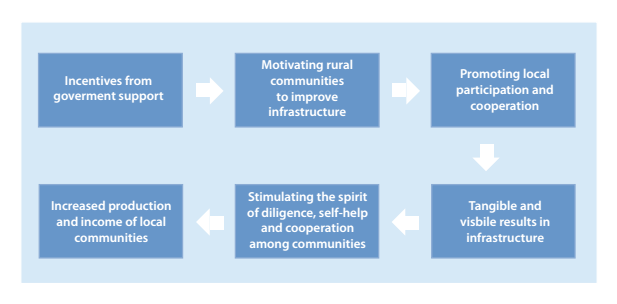

The New Village Movement’s successes can be most clearly seen as a “learning cycle of stimulus, reflection, resolution and practice”.17 Upon introducing the program, the ROK government educated the people then allowed the communities to build up their own development. The government used incentive systems that they knew would be successful, playing off of the competitive nature of the Korean people. Farmers were seen as the center of the movement, promoting the spirit of the Saemaul Movement. Eventually, the program was implemented both in rural and urban areas and at all different levels of society: village, town, county, and provincial.18 This good practices led to the six steps of the SMU virtuous cycle.

(UNDP, 19.)

(UNDP, 19.)

Due to these successes, ROK has now begun implementing SMU’s New Village Movement across Africa, Asia and Latin America.

- Sawyers, Dennis. “South Korea’s New Village Movement.” The Borgen Project. December 20, 2015. http://borgenproject.org/category/south-korea/.

- Korean International Cooperation Agency. Saemaul Undong Rural Development. Republic of Korea, 2015. Print.

- Sawyers, Dennis.

- Korean International Cooperation Agency.

- Sawyers, Dennis.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2015: “Saemaul Initiative Towards Inclusive and Sustainable New Communities: Implementation Guide.” Bureau for Policy and Programme Support, pg 13. n.d.: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/development-impact/saemaul-initiative-towards-inclusive-and-sustainable-new-communi.html.

- UNDP, 13.

- “The Saemaul, New Village, Movement Was Mindset Change.” Hyun Jin Moon. http://www.hyunjinmoon.com/saemaul-new-village-movement-change-mindset/.

- Sawyers, Dennis.

- UNDP, 11.

- UNDP, 12.

- Sawyers, Dennis.

- Hyun Jin Moon.

- UNDP, 12.

- Hyun Jin Moon.

- UNDP, 14-15.

- UNDP, 16.

- UNDP, 17.